Reframing ZURBARÁN, The Battle between Christians & Moors at El Sotillo, Metropolitan Museum, New York

Posted: 10 Jun 2024 by PML

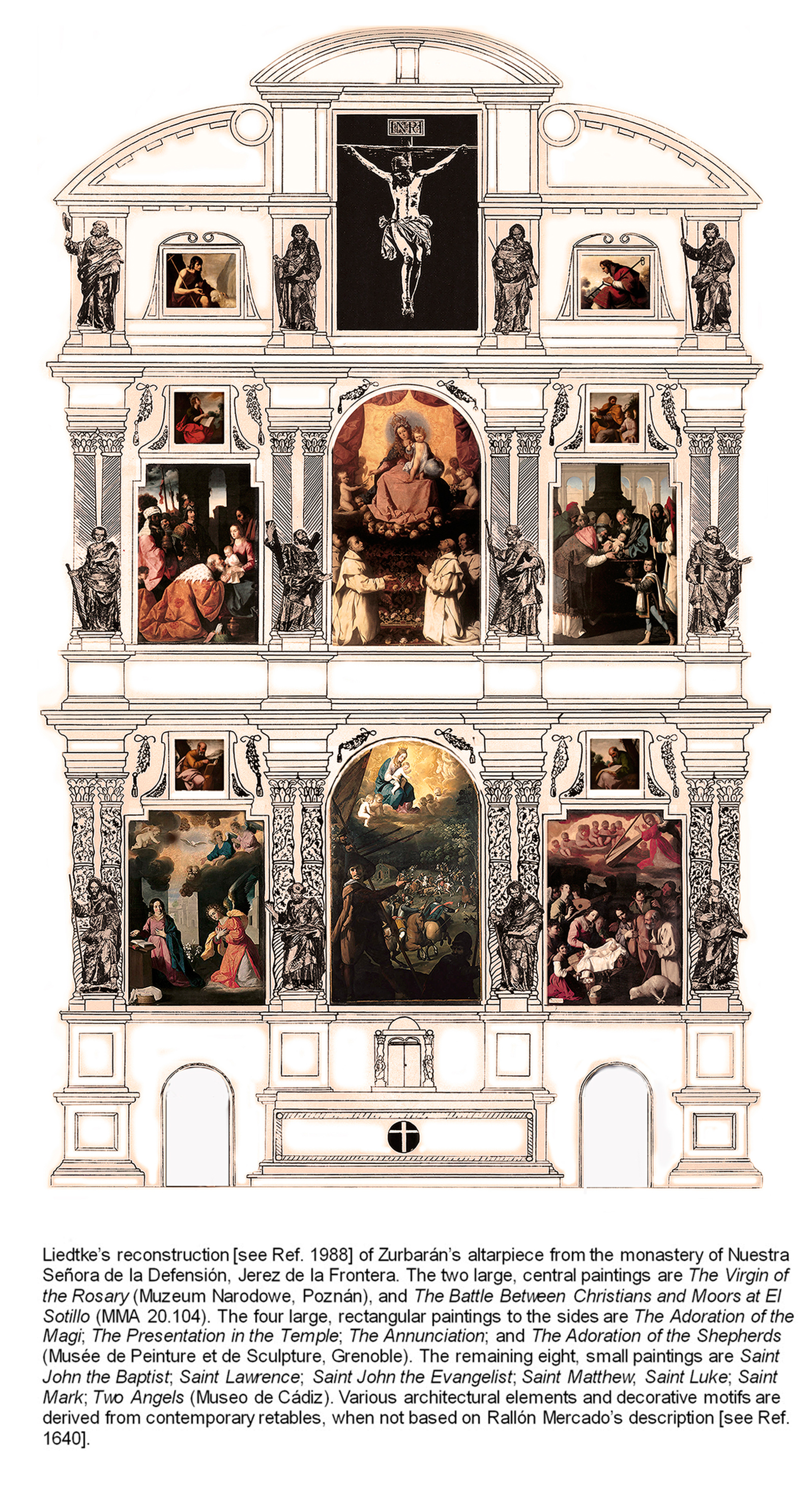

The large arched painting of the Battle between Christians and Moors at El Sotillo in the Met Museum was only one part of an immense altarpiece, about 15 metres high, painted by Zurbarán in 1637-39 for a Carthusian monastery near Cádiz.

The separate paintings were looted by Napoleon and restored to Spain after 1814, but in 1835 the whole altarpiece was finally broken up, and the various panels and sculptures dissipated to the four winds. This painting returned to France and the collection of the king, Louis-Philippe; it then travelled on to England, and was sold to the Met in 1920. Parts of an altarpiece can be difficult to frame in a manner which respects their original context, and it is usual for museums to present these works as single great altarpieces, in relatively plain frames which give them appropriate authority and presence, and focus on the power of the artist’s vision.

A painting with an arched top presents particular problems, and this one spent around a century in a frame which can only have been seen as a temporary solution until a more satisfactory one was found. It was a very narrow gilt moulding – perhaps not so insubstantial close to, but appearing flimsy and incomplete as the method of display for such a monumental work by a major artist; rather like the sight moulding for a much larger frame.

Other factors which influence a museum reframing include suiting the chosen frame to the other works around it. Many of the paintings in the Met by Murillo, Velázquez and their peers are on a much smaller scale, and are housed in elaborate and beautifully-carved Spanish Baroque frames, which - from both aesthetic and practical considerations – would have been inappropriate for the Zurbaràn Battle.

The Museum owns another large work from the workshop of Zurbaràn (not so consistently on view, but enough to be taken into account as a possible neighbour). This is the large Crucifixion which probably came from a church in Seville and which also – coincidentally – passed through the collection of Louis-Philippe. It was given to the Museum in 1965, and has been housed in a sober frame with a torus moulding at the top edge and a wide frieze, finished in black relieved by three lines of gilding.

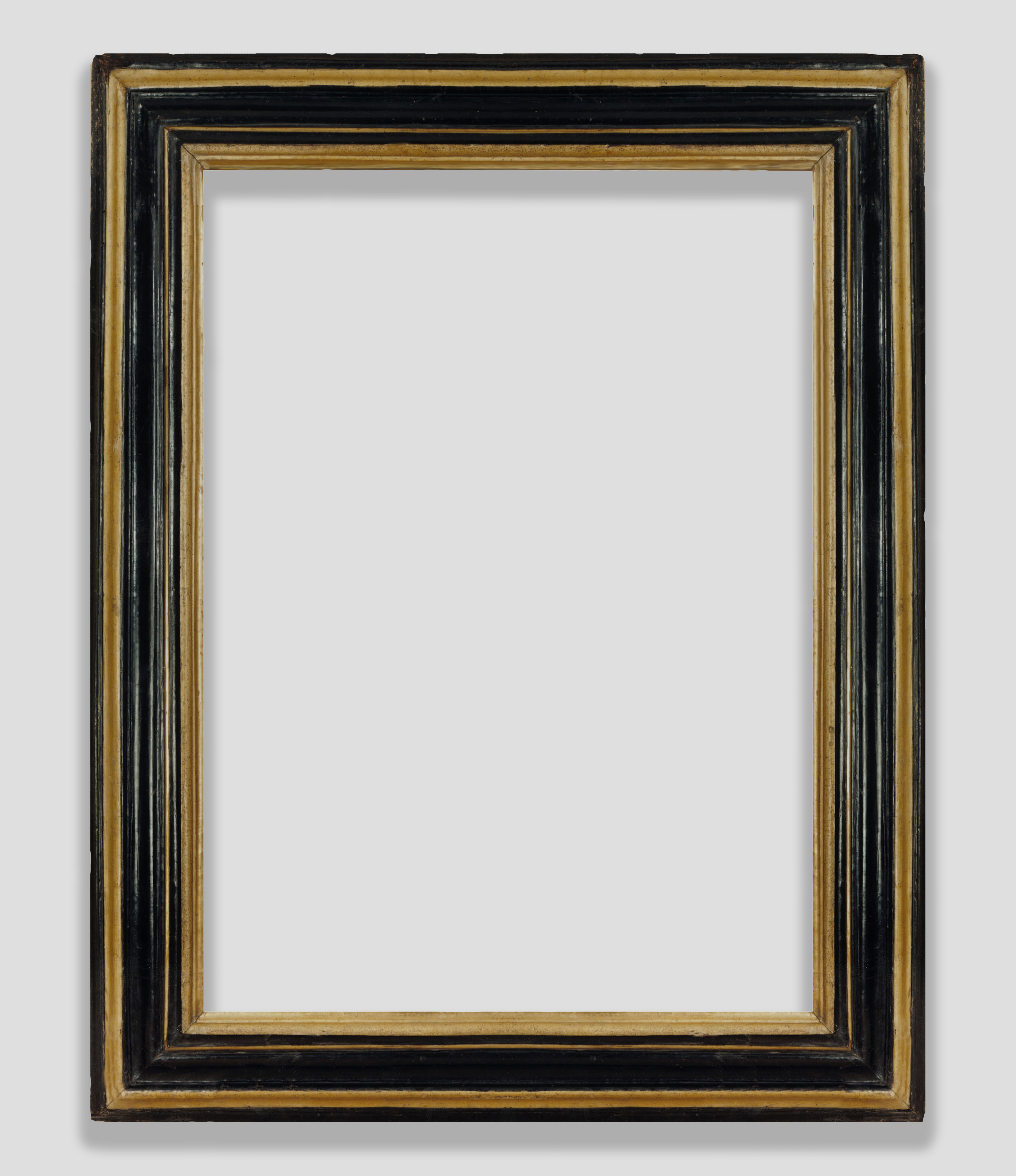

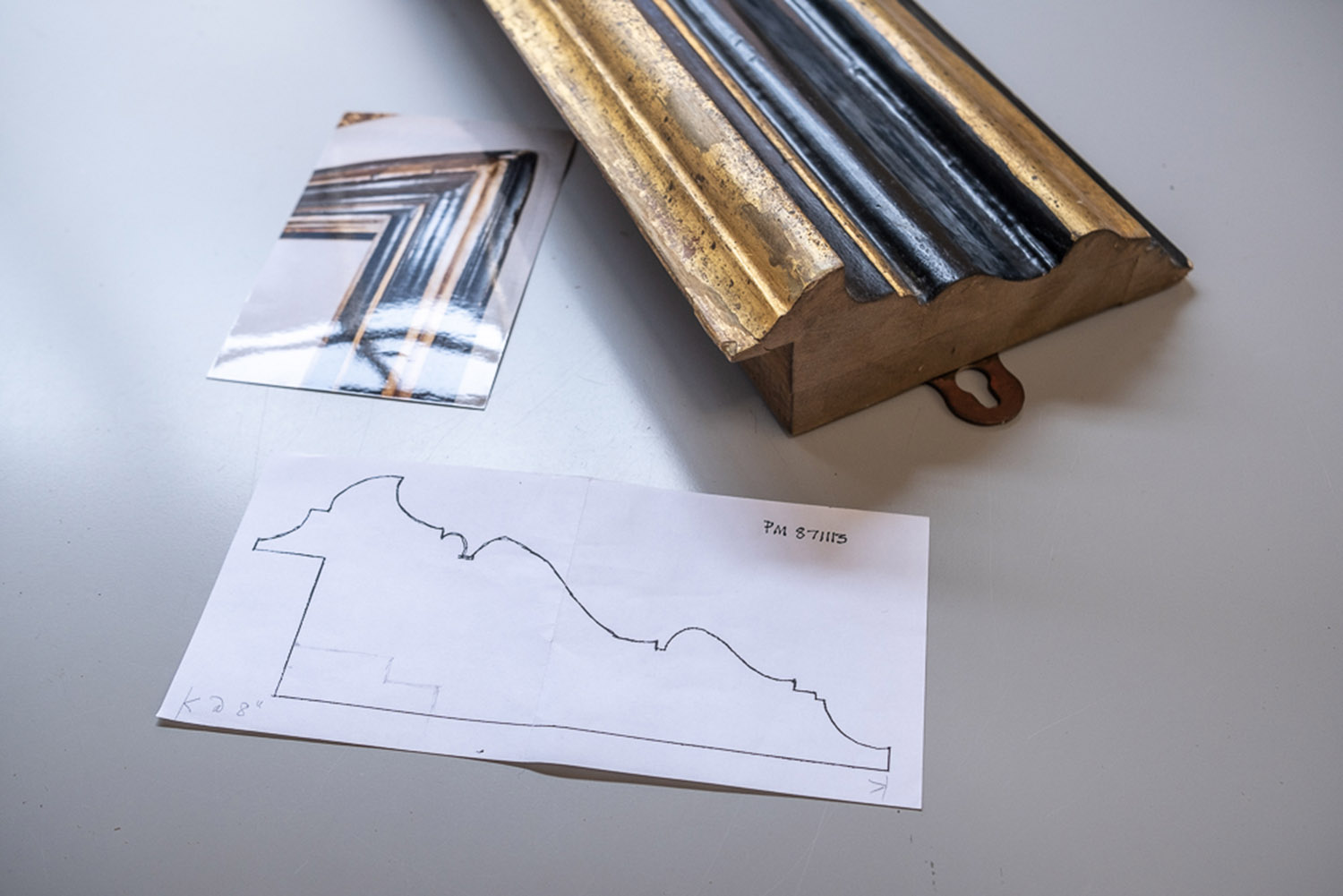

One of the frames in the collection of Paul Mitchell was a rare 17th century Baroque Neapolitan frame with a complex bolection profile, where the width of the rail was composed of descending ogee-shaped waves, falling from the top edge of the frame back towards the wall. It was finished in black with three bands of gilding, rather like the frame of the Crucifixion, but - with the complex profile and varied widths of parcel-gilt mouldings – creating a much richer and more dynamic effect than the latter. It was of the right period, and, since the southern half of Italy and parts of the far north were at that time under the rule of Spain, also appropriate through mutually-shared styles (often diffused through the Holy Roman Empire by peripatetic craftsmen, many of whom were Flemish, giving rise almost to an international fashion of frame). The profile was contained by a width of rail sufficiently wide and sculptural to display a large-scale painting, and all these advantages together caused this frame to be chosen by the curators at the Museum as most appropriate for Zurbaràn’s painting.

Further confirmation for the choice of a black parcel-gilt frame for Zurbaràn’s work comes through paintings such as this one, with its depiction of a large sacred subject in a related frame. It was executed for a monastery in Seville, the city where Zurbaràn lived and worked for around thirty years.

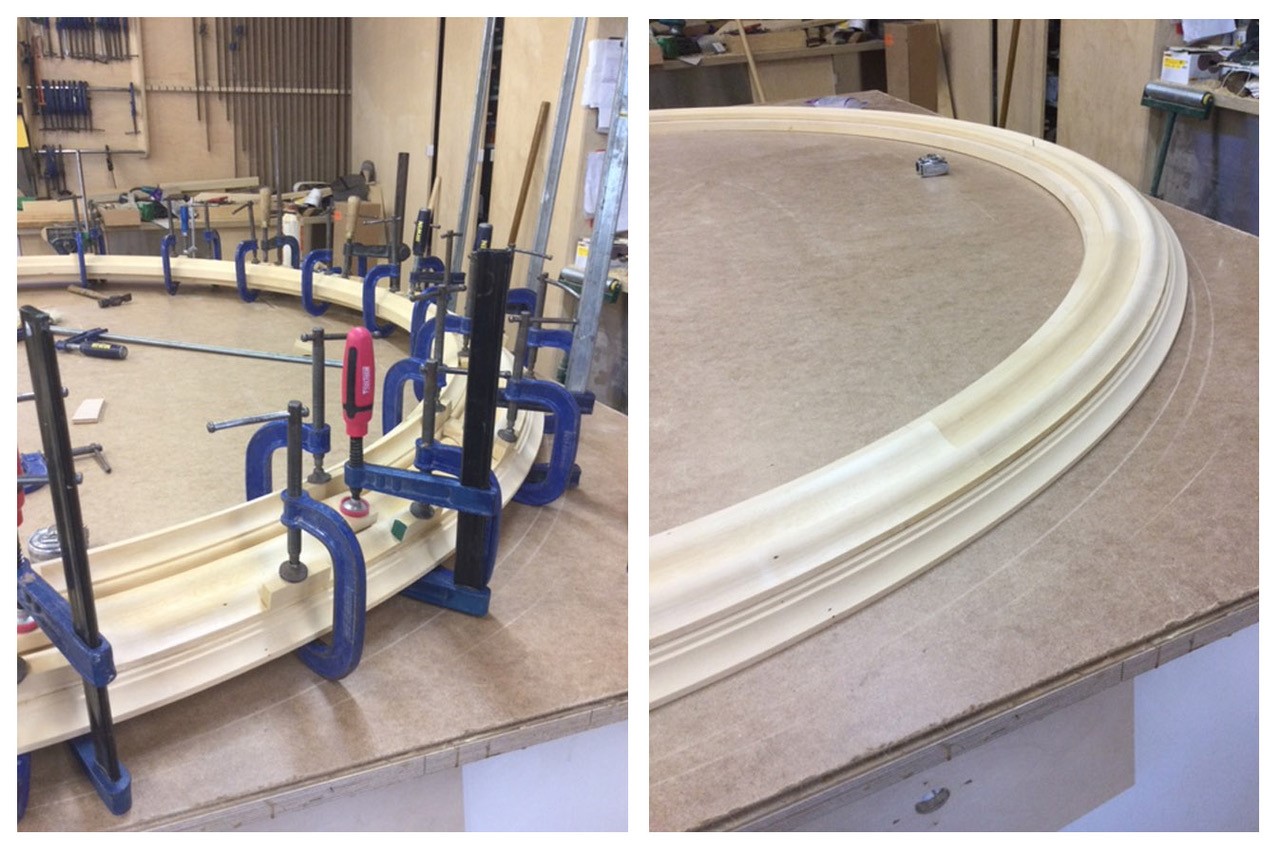

In the left-hand image above, the carved moulding for the arched top of the frame is shown fixed together with a succession of vices, to hold the curved segments in place while the glue dries. The right-hand image shows the carved arch completed.

Corners of the frame which was the model and the copy made for the Zurbaràn respectively; the latter now finished with black paint and gilding. The model (on the left) retains its original 17th century paint and gilding. In this detail, it is possible to see the extreme care which has been taken to distress both the carved wood and the painted/ parcel-gilt finish to echo the effects of age and wear on the original frame; this is because the machine-like uniformity of many modern frames sits very uncomfortably with the slight unevennesses of an antique picture, and the shiny, burnished gilding seen in some museums clashes with a work of art which has been softening and darkening by microscopic degrees over the years.

The difference the replica Baroque frame makes to the painting is immediately apparent; it appears complete in itself, as a work of considerable power and energy: a whole altarpiece, rather than a dislocated part, and one which – since it can sadly never be reunited with the other panels and sculptures in the original ensemble – can stand alone as a great painting by a great artist.