Reframing Van Gogh, The bedroom, 1889, Art Institute of Chicago

Posted: 29 Jan 2025 by PML

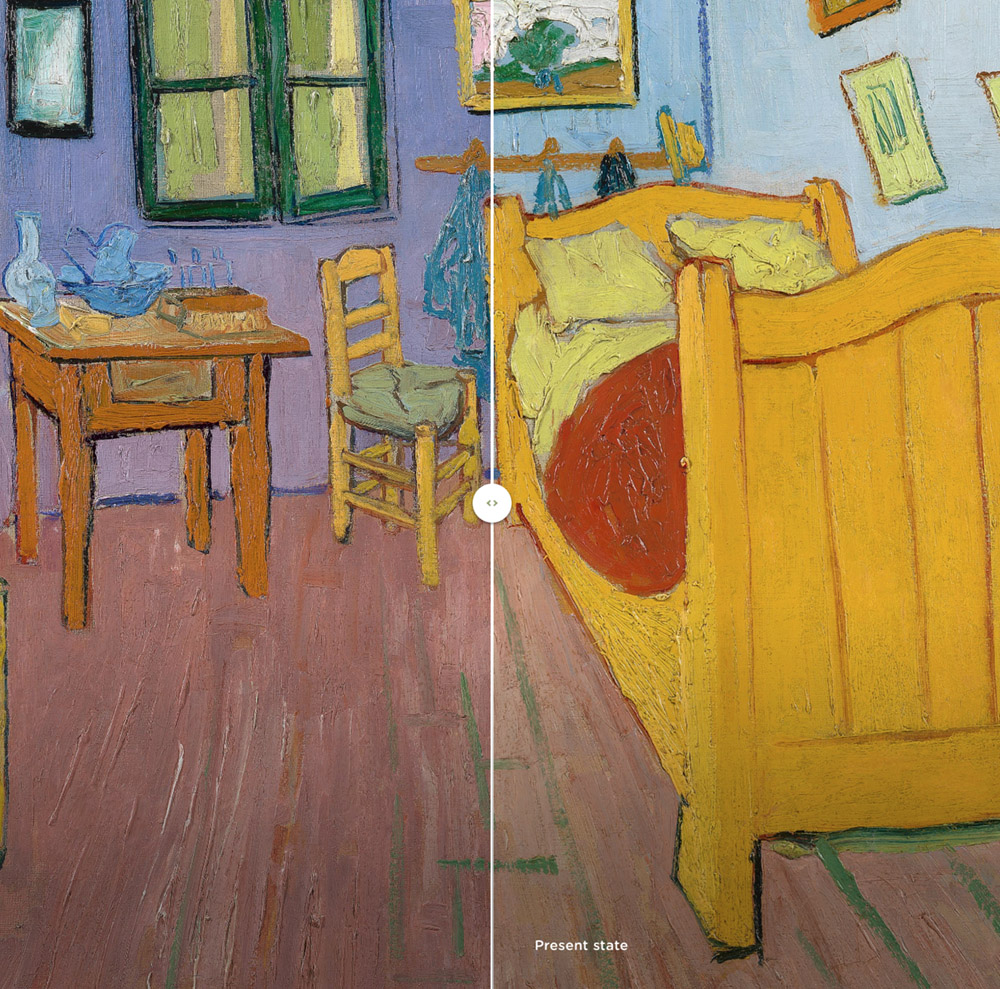

Van Gogh painted this dynamic view of his bedroom in the Yellow House at Arles three times, this one being the second version. The first painting is in the Van Gogh Museum, and its digital version on the Museum website has been provided with a sliding shutter, enabling the viewer to see what the original colours would have looked like before they were degraded by sunlight and passing time.

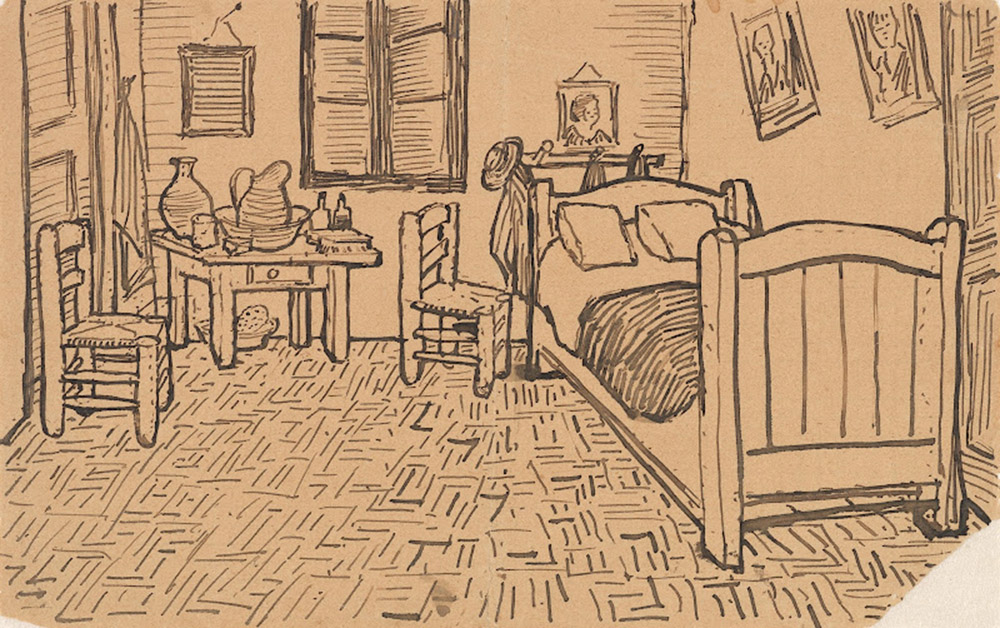

The much warmer version which this imaginative filter enables us to see makes sense of the enthusiastic letter which the artist wrote to his brother, Theo, in October 1888, including a sketch of the composition:

“...the colour has to do the job here, and through its being simplified by giving a grander style to things, to be suggestive here of rest or of sleep in general. In short, looking at the painting should rest the mind, or rather, the imagination.

The walls are of a pale violet. The floor — is of red tiles.

The bedstead and the chairs are fresh butter yellow.

The sheet and the pillows very bright lemon green.

The blanket scarlet red.

The window green.

The dressing table orange, the basin blue.

The doors lilac.

And that’s all — nothing in this bedroom, with its shutters closed.

The solidity of the furniture should also now express unshakeable repose...”

The bedroom, seen as Van Gogh painted it, is less brilliantly illuminated and chilly than in all three versions today; it is as if lighted by oil lamps or candles rather than neon, or as if entered in the early afternoon rather than at the height of a Mediterranean noon. It is more welcoming, and – as he says – ‘suggestive of rest’. The original colours also help to soften the violent perspective of the room, which, in the lighter tones and harsher contrasts of today, seem to zoom off towards the skewed back wall in the remote distance.

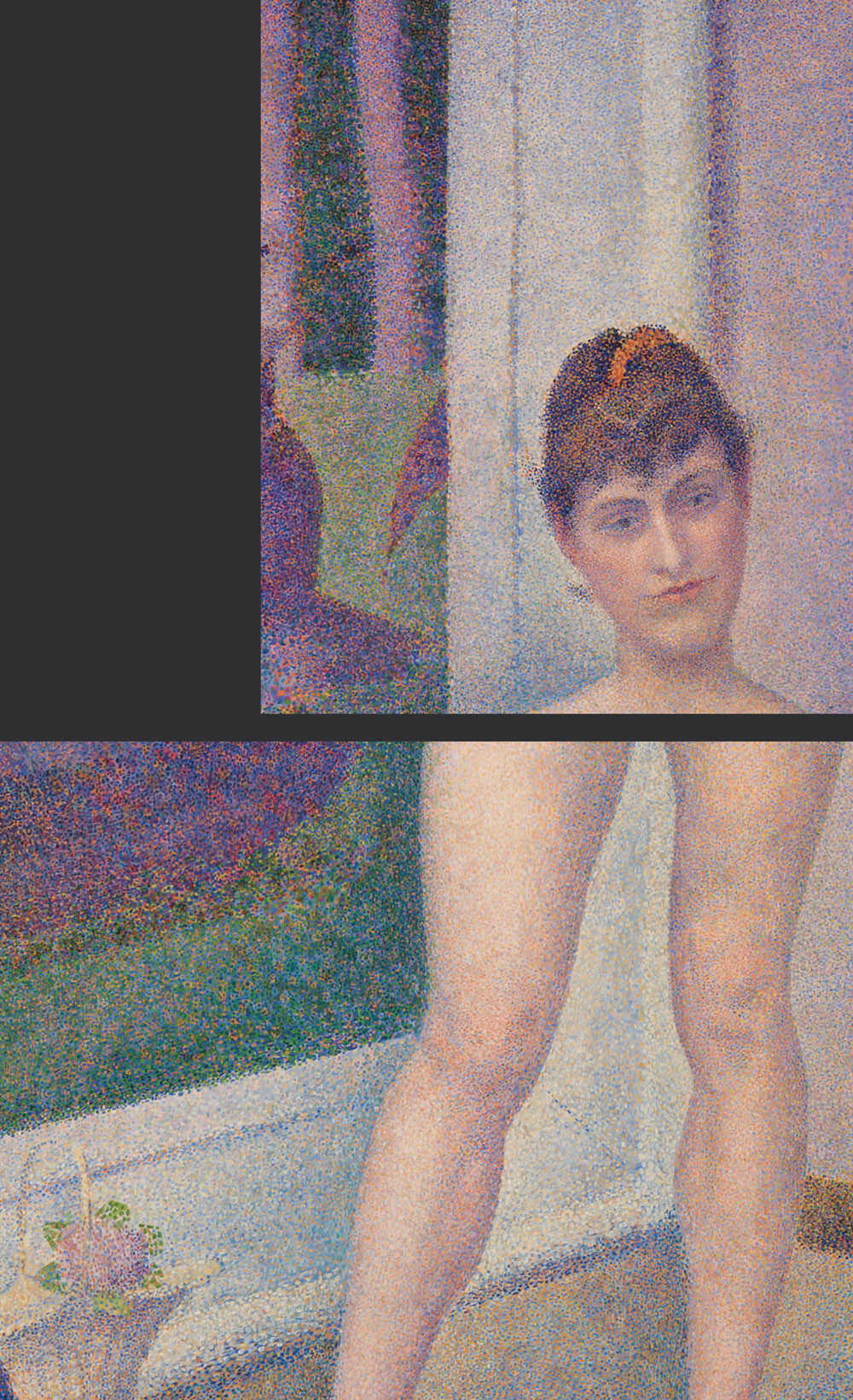

From 1873 to 1876 Van Gogh lived in London, teaching and also working for the art dealers, Goupil & Cie. In 1874 he copied a poem by D. G. Rossetti to send to Theo, and he may also have visited Christie’s, where, that same year, Rossetti’s Ecce ancilla domini was sold for £388.10s. to the Pre-Raphaelite collector William Graham. Van Gogh was drawn to the Pre-Raphaelite artists, and the exaggerated perspective of the Virgin’s bed, the use of blue and gold with a touch of strong red, and the whole composition of the room with its altered reality, all strangely anticipate aspects of The bedroom – as though a memory of them had lodged in the younger artist’s imagination and acted as a template for the peace and creativity he was seeking in Arles.

When he was in London, he almost certainly encountered for the first time artists’ frames being designed specifically for individual paintings by the Pre-Raphaelites – a practice which had also recently influenced Monet and Pissarro, in London in 1870-71/72 to get their respective families out of the way of the Prussian invasion of Paris. This new viewpoint on the way of displaying an avant-garde art at odds with the art of the academies and salons seems to have catalyzed the design of simply-made white frames amongst the Impressionists, which began to appear in their exhibitions from 1877. The fourth exhibition in 1879 included coloured frames, and more of Degas’s inventive profiles, which gave form and perspective to his frames through the light and shadow generated by linear mouldings.

When Van Gogh himself moved to Paris in February 1886, he was in time to visit the eighth and last Impressionist exhibition, where Degas was still showing paintings in frames of his own design, and Pissarro and Seurat were keeping the Impressionist white frame going. The letter which he wrote to Theo in October 1888, with the sketch of The bedroom, continues (after the description of the colours used, quoted above):

“The frame – as there’s no white in the painting – will be white.”

Unfortunately, somewhere between its sale by Johanna van Gogh-Bonger, Theo’s wife, in 1901, and its presentation to the Art Institute of Chicago in 1926, the white frame which was intended for it, and may have been applied by either Van Gogh himself or Theo, was (if it indeed ever existed) replaced by an antique French Baroque giltwood pattern with a carved design of opposed cusped scrolls and leaf buds. This was, in finish, colour and restless decoration, exactly the reverse of everything the artist had conceived of simplicity and ‘unshakeable repose’.

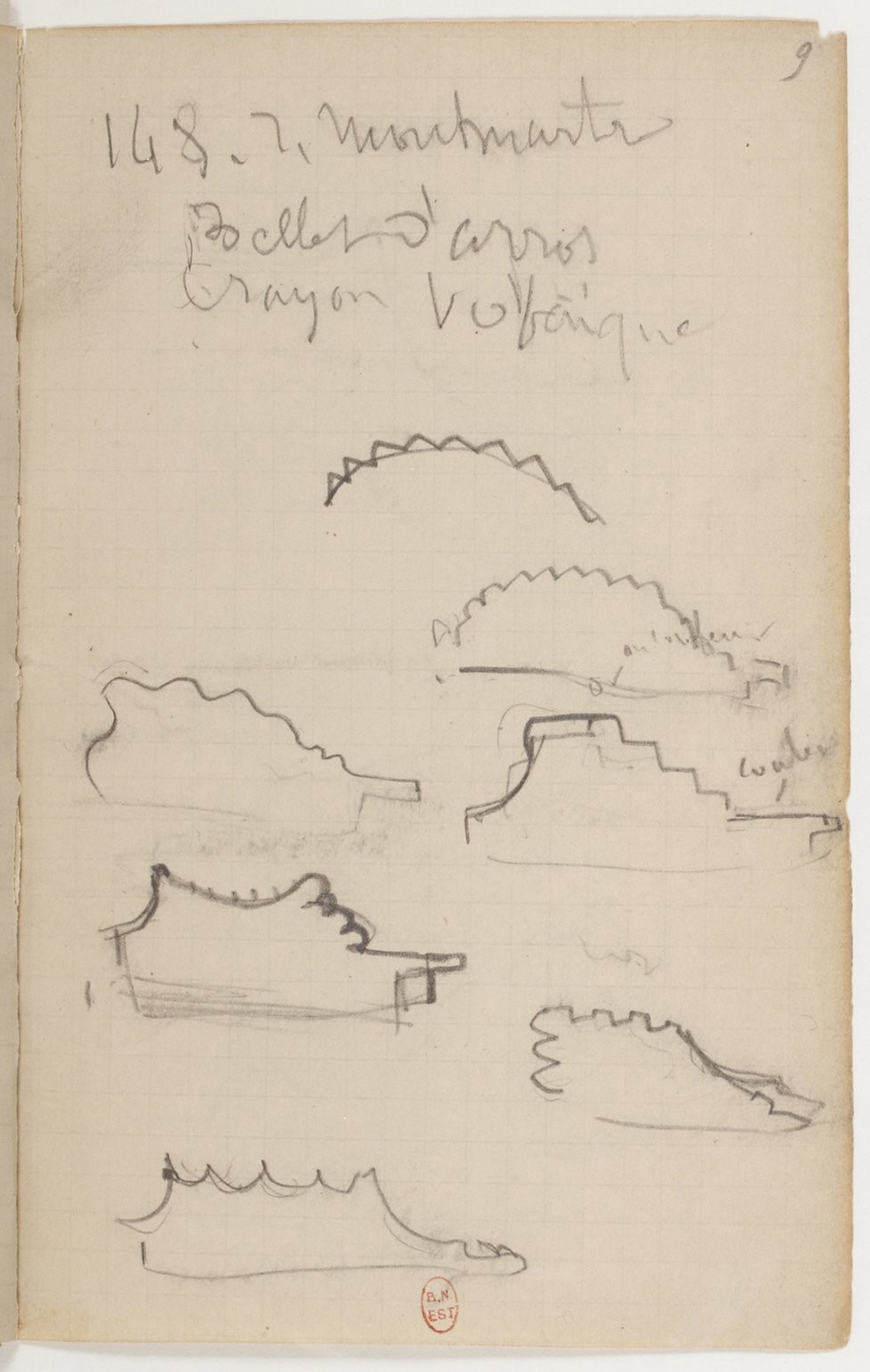

The solution offered by Paul Mitchell Ltd is an antique 19th century artist’s frame in the style of Degas’s reeded torus patterns, like that on Le tub (shown earlier), and in the top two profiles sketched above. It retained its original white finish on the gesso ground, providing the correct foil to the painted colours - just as Van Gogh had imagined, whilst the repeated lines of fine reeding give subtle reinforcement to the lines of internal architecture and furnishings, and to the perspective of bed and floor. The solid curve of the torus has the right degree of simplicity and monumentality to echo ‘the solidity of the furniture’ and the ‘grander style’ of the artist’s conception, and in all frame and painting form the perfect whole – the gesamtkunstwerk.

Categories

- Articles on multiple aspects of European frames

- Recent framing projects undertaken by Paul Mitchell Ltd