Reframing JACOB HUYSMANS, 1st Earl of Lichfield & his wife as children, 1674, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Posted: 09 Oct 2024 by PML

In 2012 this striking double portrait of a future husband and wife by the Flemish-born artist, Jacob Huysmans, was acquired by the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne. At some point in its travels, from Lichfield House in London (now part of No 10 Downing Street) via another family home (Ditchley Park in Oxfordshire) to Australia, it was encased in a very shiny ebonized moulding frame with gilt sight edge, presumably on the basis that this was appropriate for Flemish and Dutch paintings of the Golden Age in the Netherlands.

Huysmans, however, spent more than half his life and practically his whole career in England; and this was in any case a British portrait in terms of its sitters, costumes, location and original framing. The NGV – an institution which is particularly alive to the effects of stylistically appropriate framing – decided that this large and important work needed a form of presentation which was based on the patterns fashionable in Britain at the time it was painted, and approached Paul Mitchell Ltd for a solution.

The Gallery already possessed a Lely painting in an Auricular frame – the portrait of Sir John Rous of Henham Hall in Suffolk – which was painted around the time that Huysmans arrived in London, and which retained its original frame, in the pattern Lely had chosen for himself with his framemaker [1]. This made the reframing of the Huysmans portrait even more important, since it would hang near another court portrait from the reign of Charles II.

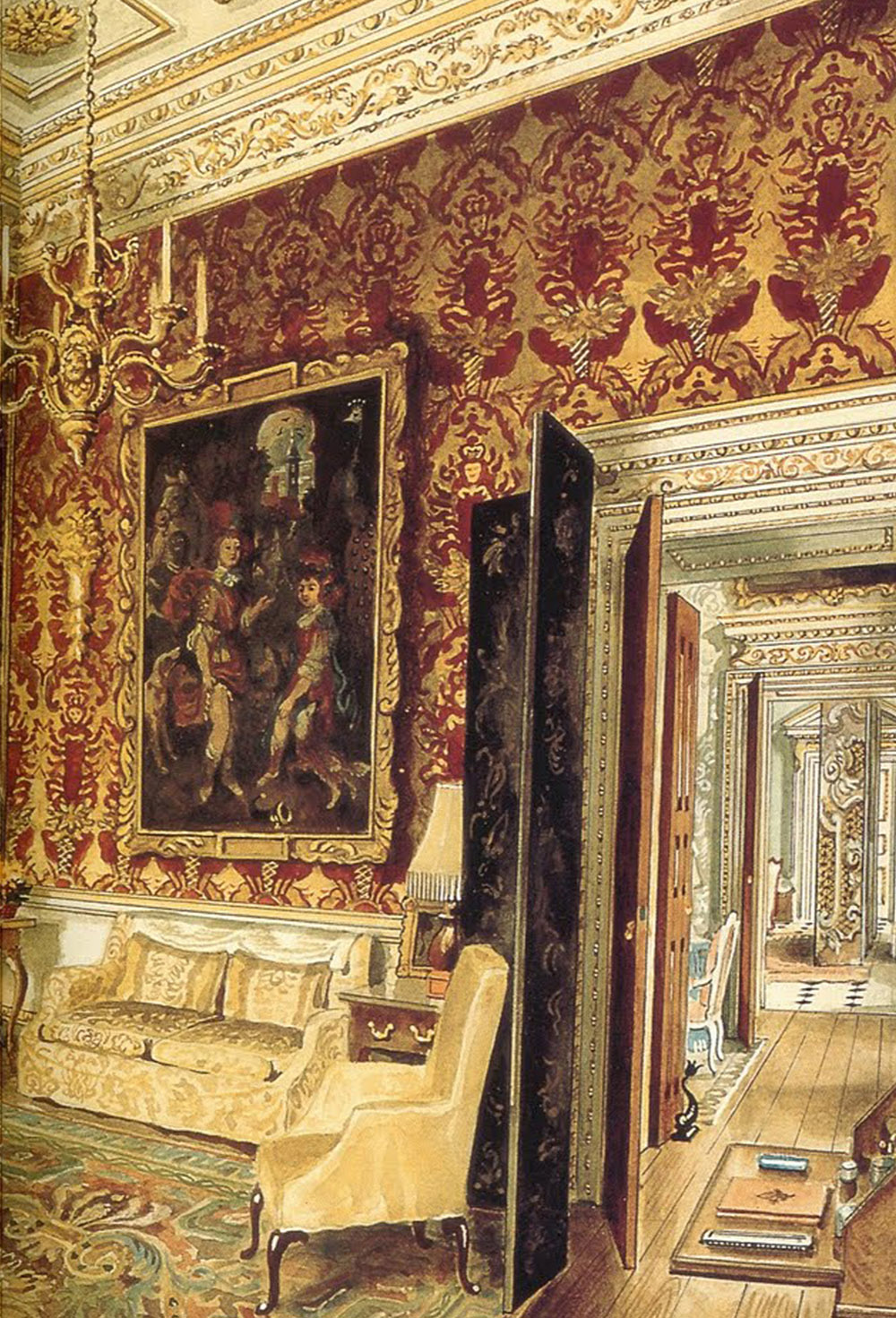

The only evidence of the first frame which had been made for the Huysmans was a watercolour painted in the 1940s by Alexandre Serebriakoff for the family which then owned Ditchley Park, where the portrait still hung. It may retain its original Auricular frame in this image – although there was also a revival in the fashion for such frames, in the 18th century and then again in the 19th [2]. Serebriakoff’s very stylized depiction doesn’t seem to follow any of the established British Auricular patterns, although this may be because of the difficulty of drawing a complex design shown at a raking angle; it may also be because the frame had been adapted and altered over the years. Whatever the reason, his painting was neither developed nor detailed enough to give more than a general idea that the portrait had had an Auricular-style frame.

Shortly after emigrating to England, Jacob Huysmans became a royal painter attached to the court of Charles II’s queen, Catherine of Braganza, and thus would have been well-placed to employ the framemakers who were also used by the king, queen, and nobility. The Norrises, for example – notably Henry Norris and his son John – were successively appointed Joiner of the Privy Chamber to Charles II and James II, making them extremely important in the supply of frames to the court circle.

They supplied ‘leatherwork frames’, as Auricular patterns were called in the 17th century, to the artists Mary Beale and Peter Lely, and also to clients such as the Duke and Duchess of Lauderdale at Ham House. It was almost certain that Huysmans would follow the example of his fellow artists and their patrons at court, and employ the king’s framemaker. But what sort of frame might he have arranged for the portrait of the small Earl of Lichfield and his prospective (and even smaller) wife?

The Earl was the son of Sir Francis Lee, the owner of Ditchley Park, and the wife, Lady Charlotte Fitzroy, was the illegitimate daughter of Charles II. The king had ennobled the ten year-old Edward Lee before the betrothal which the painting commemorates, and which had been partly engineered by Edward’s uncle, the fabulously dissolute and brilliant poet, the Earl of Rochester.

Rochester had himself been born at Ditchley Park in 1647. He had been painted by Lely in 1677, but also by Jacob Huysmans in 1665-70 in the portrait illustrated above, which had moved by inheritance from Ditchley to Warwick Castle, where it remained until sold by Sotheby’s in 2014. This portrait, still in its original Lelyesque-style Auricular frame (very probably carved and gilded by the Norrises), provided the neatest and most satisfying answer to the reframing problem. Rochester was associated with the same house and family; his portrait was painted by the same artist, and it dates to within a few years of the Huysmans double betrothal portrait. The echoes of Lely’s own frame – notably the curling snail-shell corners and the wavelike scrolls - would also be important, providing an harmonious link with the portrait of Sir John Rous in the Gallery.

As the Huysmans betrothal portrait is almost square, the Rochester frame design needed to be enlarged on the horizontal rails with elements from the frame of another ‘Lely’ style Auricular frame on another double portrait, since this is how Auricular frames were scaled up and down at the time: motifs might be elongated or compressed, and other motifs added or subtracted [3].

The frame from which the additional elements were taken belongs to Lely’s portrait of the Capel sisters from Cassiobury Park (now in the Met. in New York). An alternative would have been to use this complete frame as a model, adjusting it laterally, although of course it lacks the connections of the other frame, and the foliate motifs look rather lacklustre. Basing the pattern primarily on the Rochester frame also meant that the motifs which differed from Lely’s designs but occurred in one used by Huysmans would be retained, which was a more satisfying solution.

The frame was carved and gilded by two of the world’s best artists, the details of the models for all its elements meticulously reproduced, and the gilding and toning indistinguishable from the patina of age on the small 17th century frame. The latter, and the height of the room and window in the photo above, demonstrate quite how large an object this is, and the work involved in transferring, on a proportionate scale, the flowing, melting motifs of the Rochester frame onto a frame which is half as high again, and seven quarters as wide.

The portrait after reframing shines out, having miraculously gained greater space and depth; not to mention the magnetic, eye-drawing emphasis which the glowing gold margin gives to the painting, and the restoration of its historical context. There is no interior full of furnishings for the frame to echo; instead we see the consonance of form in the levitating swags and curls of the children’s cloaks and sleeves, the plumed hats and the curve of the hunting horn in the foreground, all reflected in the folds and scrolls of the frame. The peacock’s tail and the drooping dogs’ ears also seem to be repetitions of the carved motifs, as if to underline the organic nature of the Auricular style, and its roots in the scientific interests of the late 17th and the 18th centuries.

Expeditions to gather objects for the wunderkammers of Europe, advances in anatomical knowledge and curiosity about marine creatures all played a part in generating the language of the Auricular – the shells, sinewy forms, wings and bones, segmental shapes, mascarons of monsters and Green Men were all in some sense indications of the refined knowledge and avant-garde interests of the patrons sophisticated enough to use this language. Restoring to this double portrait a version of the Auricular frame it would undoubtedly have possessed originally helps to connect it closely to court life and ideas in the 1660s-80s, points out the young Earl of Lichfield as a possible patron of the Royal Society (founded in 1660), and reminds us that the little girl is the beloved, if bastard, daughter of the king.

References

[1] The Lely frame is original and of 17th century manufacture, although it was recut on some of the plain surfaces in the 19th century

[2] See Christopher Rowell, ‘Notes of the revival of the Auricular style for picture frames’, Auricular style: frames

[3] Jacob Simon, ‘Documenting developments in the taste for Auricular framing in Britain, 1620-80’, Auricular style: frames https://auricularstyleframes.wordpress.com/2016/12/27/documenting-developments-in-the-taste-for-auricular-framing-in-britain-1620-80/

Categories

- Articles on multiple aspects of European frames

- Recent framing projects undertaken by Paul Mitchell Ltd