Reframing GABRIËL METSU, Lucia Wijbrants, 1667, Minneapolis Institute of Art

Posted: 04 Dec 2024 by PML

This portrait - although the sitter’s identity was only recently discovered - turns out to have descended in her family for two hundred years, almost certainly retaining its original frame, until it was sold to a member of the Rothschild family in 1865. The fashion then was to ‘update’ Netherlandish paintings from the plain and elegant ebony or fruitwood frames given by the artist or bought on behalf of the client, and fit them out with gilded French Baroque frames. In these new garments they would blend happily into an 18th or 19th century collector’s picture gallery, amongst the paintings he or she had acquired in Paris or Rome; and would echo the giltwood period furniture which now surrounded them.

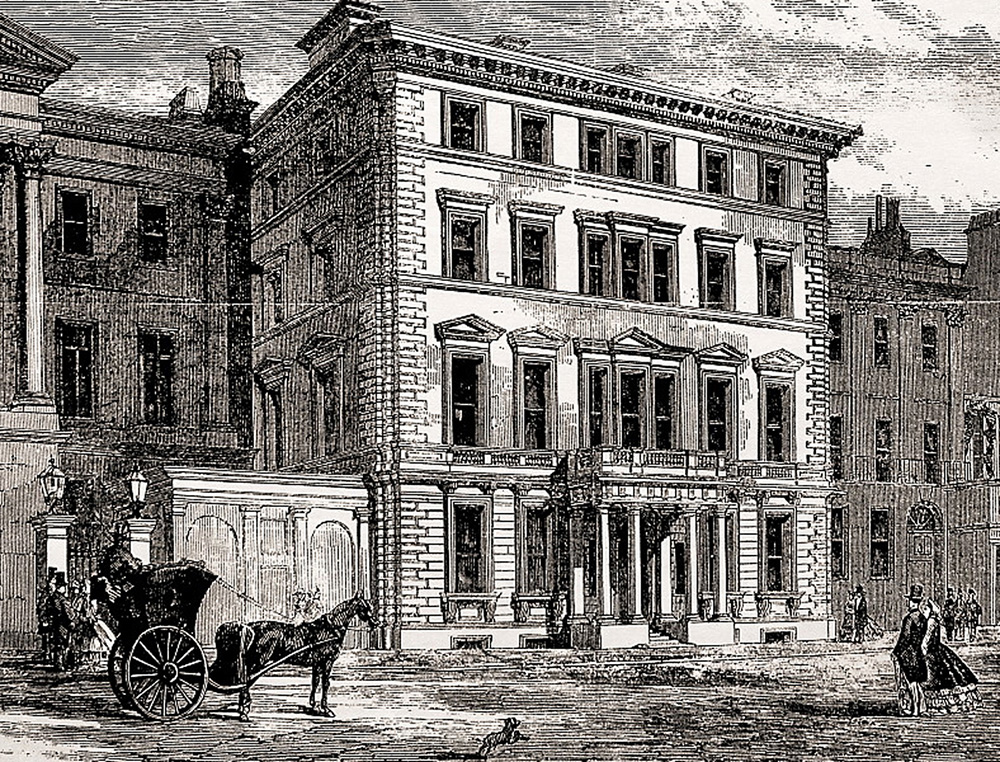

Baron Lionel de Rothschild (1808-79) was a banker, MP, collector of objets d’arts and philanthropist, who also collected paintings – a group of British portraits, works by Greuze, and by Cuyp and De Hooch as well as by Metsu. He bought the portrait of Lucia Wijbrants from a descendant of the sitter, passing it down through his own family until it was sold again in 1937.

Although it had various later homes in England and America, the likelihood is strongest that it was given its previous (very beautiful, but unsuitable) Louis XIV giltwood frame whilst in the possession of the Rothschilds of Piccadilly, in order to fit it into their opulent mansion, next door to Apsley House.

Metsu paints scenes set indoors and outdoors, sacred subjects, and figures in all sorts of interiors, from high to low; his work is always engaging, beautifully composed and lit, and the details of the furnishings in the rooms he depicts are meticulously executed.

These are rooms which – in the case of middle- and upper- class settings - are hung with paintings where the frames are shown in as careful detail as the paintings they hold, indicating for any of his clients or later collectors the styles he knew and expected for his own work. They include large overmantels in narrow gilt mouldings; golden Auricular frames carved with melting loops and swags and shell-like forms, and plainer ebony or dark wood frames on pictures and looking-glasses.

Perhaps his best -known and -loved pair of paintings, in the National Gallery of Ireland, which show the writing and reception of a love-letter by a man and a woman, also show analogous but differing frames – a richly ornamented Auricular frame on a tranquil landscape, and a curtained ebony frame on a stormy seascape with a small black looking-glass beside it. The gilded frame accompanies the black-suited man; the black ones hang beside the colourfully-clad and bejewelled woman - whose coral skirt is bordered with a sparkling frame of gold - in a wonderful play of oppositions. The black frames are described in detail, with their profiles (pushing the looking-glass forward from the wall, or hollowed back around the seascape) realized in three dimensions.

In another work, in the National Gallery, London, the landscape hanging in the background has an ebony frame where the profile seems to billow in a series of wavelike steps or ogees, the parallel lines of light produced by these shapes helping to focus attention on the painting within.

These painted portraits of frames provide an indication for how the portrait of Lucia Wijbrants might best be framed, her own sparkling, gold-laden costume and fair hair having been almost extinguished by the giltwood collector’s frame which competed with her brightness for so long. Rather than a black border, however, the perfect solution was found by Paul Mitchell in a 17th century Netherlandish ebony frame with a rich russet-brown tone and handsome figuring in the grain of the wood. This echoes and provides a variation on the warm colouring of the painted interior – its furnishings, floor and carpet – and a foil to the standing figure in its dress of silver and pale gold.

This frame has a Baroque structure, with a small outer moulding and a large central ogee, which sweeps down in a curving S-shape to the sight edge. The softness of its rounded forms, the warm colouring and satin-like finish of the frame ensure that, instead of fading back behind the gilded Louis XIV frame, the figure of Lucia Wijkbrants now shines out against her background in regal splendour.

As Dr Rachel McGarry says – the curator in charge of European art at Minneapolis:

‘The painting looks absolutely stunning in our galleries now. The period frame you found complements the picture rather than competes with it, and allows the viewer to see subtle details in the exquisite interior in the background, especially in the shadows, which were somehow obscured by the bright gilded frame’.