A Concise History of Frames

Mediaeval & Renaissance frames

Ornamental borders have been used to define works of art for around 4,000 years or more, but the ancestors of the modern carved wooden frame appeared only from around the 11th century.

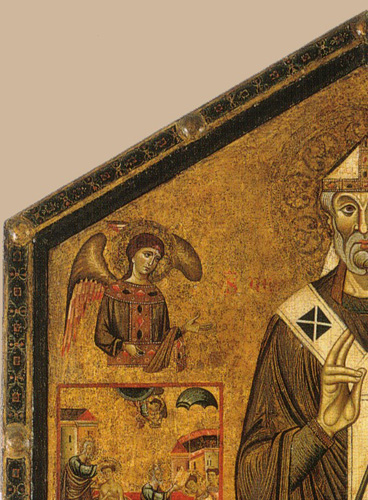

Master of San Verano, The life of San Verano, c.1275, Pinacoteca Brera

These were the raised edges protecting a painted wooden altar (the frontal); this pictorial surface eventually moved up to become a framed painting on top of the altar (the dossal), and the border grew progressively more ornamental – and more like a church in silhouette.

Taddeo di Bartolo, Assumption of the Virgin, 1401, Duomo, Montepulciano

Gradually this aspect was elaborated, articulating painted panels which were arranged like the aisles and chapels of a church around the main picture (or nave), and forming tiers, like the clerestory of a church. At this point frame and painting were indivisible in their physical, narrative and symbolic connection, and the carver, gilder and artist contributed their work on equal terms.

Domenico Ghirlandaio, Adoration of the shepherds, 1485, Santa Trinità, Florence

The Renaissance, which was a rebirth of classism in all the arts, including literature and philosophy, influenced not only artists to depict the story they were interpreting on a single unified surface, but also architects (and through them the framemakers) to employ the rectangular forms and harmonious proportions of classical temples. The frame now acted as a door or window opening onto the naturalistic world of a single scene - the sacra conversazione – and it was no longer bound to the painting but removable: the beginning of the modern picture frame.

Antonello da Messina, Portrait of a young man, c.1470, Metropolitan Museum of Art

When secular works (portraits, and then history and still life paintings) began to challenge the supremacy of the altarpiece, simpler frames were required, and were adapted from the borders of small sacred paintings and from the inner margins of classical altarpieces. These early designs – recognizably very close in section to those we use today – consist of a flat or gently curved frieze between raised mouldings of more or less complexity. They are known, in their Italian form, as cassetta frames. Although very simple in construction, they provide endless opportunity for decoration: the mouldings (possibly the frieze, as well) might be carved with one, two or multiple orders of ornament; the frame might be entirely gilded, or parcel gilt and painted; paint might be applied over the gilding, and designs scratched through to the gold beneath (sgraffito decoration), or gold patterns applied on top of the paint. Designs might be engraved into the gilding, or motifs might be punched, with the effect of fine brocade. An early form of moulded ornament (pastiglia) might also be applied to the wooden carcase; and raised designs created with liquid gesso. If the frame were executed in a more luxurious wood, such as walnut, this might be finished with stain and polished, and perhaps picked out with gilded details.

Every nationality developed its version of the cassetta frame, just as every country had produced its own Gothic and Renaissance style of altarpiece.

Mannerist and cabinetmakers' frames

Tintoretto, Susanna bathing, 1555-56, Kunsthistorisches, in ‘Sansovino’ frame

However, as the harmonious proportions and refined decoration of the classical Renaissance moved into the subversions of the later Mannerist movement, more distinctive national variations became apparent. Italian Mannerism played with distortions of classical motifs, and experimented with the optical effects achievable through exaggerated ornaments – such as the emphatic scrolls and fluting of the ‘Sansovino’ frame, above…

Van Dyck, The Countess of Southampton, c.1638, Fitzwilliam Museum, in British ‘Sunderland’ frame

…whilst British Mannerism took on a softer, flatter appearance, weaving Italian-influenced scrolls with Auricular ornament and decorative foliage, and ending in the characteristic swirling and segmental decoration of the ‘Sunderland’ frame.

Cornelis van Ceulen, Cornelia Schade, 1654, Rijksmuseum Twenthe, Enschede, in Netherlandish Auricular frame

The Netherlandish versions of Auricular frames were influenced, amongst other things, by the melting and fluid silverware produced for the court of the Holy Roman Emperor, Rudolf II of Bohemia. These combined the cartilaginous motifs, which give Auricular ornament its name, with marine motifs which look to Italian Mannerism.

Bartolomeus van der Helst, Portrait of a woman, 1656, Städelsches Kunstinstitut, Frankfurt

However, there were other less sculptural frames being produced simultaneously with these virtuoso carvings; Northern countries, such as the Netherlands, Britain, Germany and Austria, had used very simple cassetta-style frames until the early 17th century, which might be painted (often black or an earthy colour), polished or parcel-gilt. The increased trade with New World colonies which marks the 17th century introduced a variety of new and exotic woods to northern Europe, such as ebony and amboyna wood; these appeared first as off-cuts, which were very suitable for picture frames, and soon the painted cassetta was supplanted by the stained and polished cabinetmaker’s frame. These might be enhanced by the first machine-carved ornament – runs of small ripple and basketweave mouldings (above), which can become very elaborate in German and Austrian frames. Other embellishments included silver and ivory inlays, applied ornaments and tortoiseshell veneers.

Reni, The angel appearing to St Jerome, c.1638, Detroit Institute of Art, in Italian Baroque frame

Baroque & Palladian frames

The distorted classical forms of Mannerism gradually became more and more organic, until they merged with the naturalistic ornament of the Baroque style. Baroque buildings employ stepped and receding rather than flat façades, and the same dramatic light-sculpting profiles were used for Baroque frames.

Rubens, Matthaus Yrsselius, c.1624, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen, in French Baroque (Louis XIII) frame

With this stylistic movement, the work of French craftsmen became particularly sophisticated and influential, so that we find Louis XIII frames with prominent convex and concave mouldings, decorated with garlands of bunched, cross-cut or undulating leaves.

Velasquez, Don Pedro de Barbarana, 1631-33, Kimbell Art Museum, in Spanish Baroque polychrome frame

Baroque Spanish frames similarly employ a rolling profile, often with a central hollow, as well as dramatic, opulent, and fluidly-carved leaf ornaments. As in Louis XIII frames, these may run around the entire frame, or – a feature of Baroque frames – they may highlight the corners, and sometimes the centres as well. Spanish frames are noted for their polychrome finishes, which further emphasize the carved panels of the frame, enabling these to create an optical interplay with the compositional lines of the paintings they contain.

Rigaud, François Girardon, 1705, Musée des B-A, Dijon, in French Baroque (Louis XIV) frame

Polychromy was never fashionable for French Baroque frames, but Louis XIV styles began to develop similar corner emphases to those employed in Spain. In this case, however, the corners began to project beyond the linear silhouette of the contour, with subtle, curving outlines which reflected the brocade-like patterns of carved foliate ornament covering the body of the frame. This ornament was greatly influenced by designers such as Jean Bérain, and engravings of his work promulgated the style widely, allowing it to be adopted for many types of object, material, and finish. Versions of Louis XIII and XIV frames became popular across Europe, including Britain, where a more shallowly-carved, less plastic ornament was common.

Allan Ramsay, Thomas, 2nd Baron Margam & his siblings, 1742, Tate, in ‘Kent’ frame.

Also popular in Britain in the early 18th century was the more classically-derived Palladian frame. This had grown from the Mannerist tendencies of Michelangelo’s architecture, Spanish frames in the ‘Herrera’ style and Netherlandish decorative designs, as well as from Palladio’s villas in the Veneto. All these influences came together in the work of Inigo Jones and of his disciple William Kent, giving rise to the ‘Kent’ frame. The hallmarks of this family of designs are a flat, architrave profile with a wide frieze, sometimes carved (as above) but often sanded, often with outset corners, bold architectural mouldings, and the occasional carved shell or patera.

Examples of Roman 'Salvator Rosa' frame: plain 'gallery frame' (right) & with 5 orders or ornament (left)

A classicizing form of Baroque frame was also extremely popular in Italy, from the late 17th century onwards. This is the ‘Salvator Rosa’ pattern, known (like the ‘Sansovino’ frame) by association with works by the artist, rather than because he designed it. Like the British Palladian frame it is linear in its silhouette and organization of its ornament, but it has a very different and characteristically Baroque profile, formed of stepped ogee and convex mouldings around a deep scotia or hollow. In its very plainest form, with no carved ornament, it became the chosen form of gallery framing in the great Roman palazzi, providing an attractively uniform setting which could integrate a disparate collection of paintings within a state apartment. It could, however, reach an apogee of opulence, with carved decoration on every moulding, sometimes combined with or replaced by painted and faux marbre finishes.

Jean-Marc Nattier, An allegory of Justice combating Injustice, before 1748, Sotheby’s London, 3 July 2013, in Louis XV frame

In France the Baroque style of frame generally eschewed the straight-edged silhouettes of Palladian and ‘Salvator Rosa’ designs for a curvilinear outline, developing the projecting corners and centres of Louis XIV patterns into the great sculptural cartouches of the Louis XV frame (although there are economical variants using the Louis XV profile in a linear format).

Details of ornament and finish on Louis XV frames

Rococo frames

Under this movement towards curving and scrolling lines, the straight top edges of the frame began to break down into a series of ‘swept’ rails (C- or S- curves) which echoed the corner motifs; the surface of these mouldings, of the hollows and of the corners themselves accreted finely carved ornament, and in addition were engraved or punched with further decorative textures. This was the age of the maître-sculpteur or master carver; the répareur, who recut detail into the gesso which coated the mouldings before gilding; and of the doreur or gilder himself, who might add punchwork as well as employing different shades of gold, and matt or burnished finishes. The craftsmen who produced the grand-luxe frame - more a sculpture in its own right than a mere border - worked for the Bâtiments du Roi, from which a pitch of virtuosity was expected; they carved whole interiors of intricate panelling, or boiseries, or which the frame was a vital part, focussing attention on the painting.

Francesco de Mura, Count James Joseph O’Mahoney, c.1748, Fitzwilliam, in Italian Rococo frame; Jean-Etienne Liotard, Jean-Louis Buisson-Boissier, 1764, Houston, in French High Rococo frame

The apogee of this style was the Rococo: asymmetric, subsuming structure into ornament, and ever more flamboyant, it echoed the sweep and swirl of 18th century costume, stucco, furniture and metalwork. It included watery and pierced motifs, shells and rocailles, animals, birds, floral and foliate decoration which looked towards a contemporary and philosophical ideal of nature.

Johann Valentin Tischbein, Graf Fries and his family, 1752, Kunstmuseum, Düsseldorf, in German Rococo trophy frame

The Rococo was widely diffused throughout Europe and America, taking different emphases as it was adopted by different countries; in the states which made up modern Germany, in Middle Europe and in Scandinavia, the use of exaggerated asymmetry and flyaway cartouches was even more pronounced than in its native France.

Classicizing & NeoClassical frames

Sir William Orpen, Le chef de l’Hôtel Chatham, Paris, 1921, Royal Academy, in 18th century British ‘Carlo Maratta’ frame

Britain retained a strong predilection for classicizing style, restraint and order, which caused Palladian architecture and applied arts to flourish alongside the Rococo; this also predisposed British collectors to choose versions of the Roman Baroque ‘Salvator Rosa’ frame as an alternative to the Rococo. This pattern had been brought home by collectors on the Grand Tour (as with the Batoni, previously), and it was naturalized under the appellation of the ‘Carlo Maratta’ frame, becoming a particularly popular setting for portraits during the last third of the 18th century (and subsequently). Like the Roman ‘Salvator Rosa’ frame, it was produced with varying degrees of enrichment.

Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, La comtesse de la Châtre, 1789, Metropolitan Museum, New York, in Louis XVI fronton frame

This enduring taste for the classical, along with a reaction against the extravagances of the Rococo in the 1750s-60s, combined with an upsurge in the contemporary study of antiquities to catalyze a new phase of classicizing style, or NeoClassicism (in France, le style Louis XVI). Excavations had begun at Herculaneum in 1738, and a set of engravings of the findings were published in 1753-54, along with images of Roman ruins by Piranesi (1748), and associated collections by the Comte de Caylus, and Robert Adam. French NeoClassical ornament was relatively weighty and austere, and frames in the style retained something of this (above); Roberts Adam and his brother James promulgated a lighter version of NeoClassicism.

Ingres, Mlle Caroline Rivière, 1806, Musée du Louvre, in Empire frame

Although French NeoClassicism was associated with the reign of Louis XVI, it surivived the carnage of the French Revolution to be remade by designers such as Percier and Fontaine, Napoleon’s official architects, first as the Directoire and then as the Empire style. Frames of this genre were characterized by opulent but shallow-relief decoration, the makers of which took advantage of the growth in moulded composition ornament during the late 18th century to produce a style suited to a new age of less conspicuous luxury, which would be more economical and more widely available to the rising middle classes. This style spread, not so much as hitherto through travelling craftsmen or books of engraved ornament, but via the growth of the Napoleonic Empire, and through necessity caused by the effects of war, devalued currencies and interrupted trade patterns.

The 19th century & artists' frames

Carved reverse boxwood moulds for composition ornament, 19th century British, private collection

Rather than executing a single frame in the form of a unique sculptural work, carvers were now required to produce the wooden moulds for applied compo ornament. Their numbers fell radically over the twenty or so years up to 1813 - reduced in London, for example, by almost 90%. This change was echoed by the industrialization of other frame-making processes during the early 19th century, helped by Samuel (brother of Jeremy) Bentham, who in 1793 patented a large number of mechanical woodworking devices and was helped to develop them by Marc Isambard Brunel. The effect upon frames of industrialized processes, particularly the increasing use of compo for what had been hand-carved ornament, is illustrated by Thomas Lawrence’s changing frames. In the 1790s he had used a wide, fully-carved version of a ‘Carlo Maratta’ – for example, on his full-length portrait of the 5th Duke of Leeds (1796); but in the 1800s a scotia or hollow frame with monumental foliate corners and shallow surface decoration in compo on, for instance, Lord Castlereagh (1809-11).

Studio of Lawrence, George IV, 1820-30, Chatsworth; detail of a Lawrence frame

By the 1810s he had arrived at what is known as the ‘Lawrence’ frame: a wide ogee covered with a skin of delicate scrolling foliate motifs, which would have a great influence on framing in Britain during the first half of the 19th century.

The economy of producing compo ornament meant that Old Masters could be easily reframed (often anachronistically), and that exhibitions across Europe came to look like coloured walls, the bricks held together by wide panels of golden mortar. Revivalist styles predominated, as it was simpler to copy than to innovate: NeoClassical, NeoGothic, troubadour and Renaissance, French revivals or ‘neo-Louis’. Reaction against cheap manufacture allied to this lack of imagination began amongst artists in the first decades of the 19th century; Frenchmen such as Auguste Couder and Victor Orsel, and German Nazarenes such as Franz Pforr designed their own frames, in order to create an appropriate and contemporary setting which would be one with the whole work of art. The Nazarenes in particular were influential for the most important artistic movement, relative to frame design, of the 19th century – the Pre-Raphaelites.

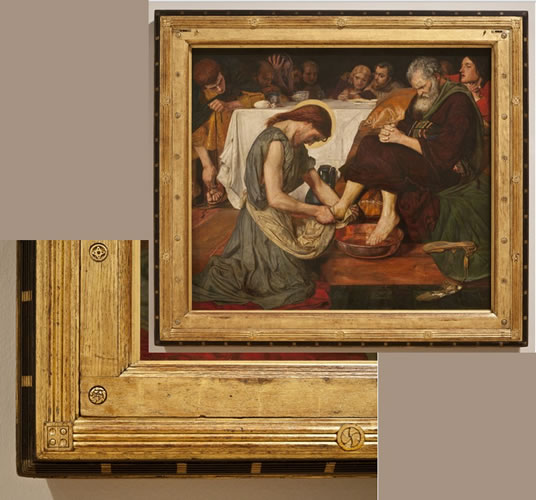

Ford Madox Brown, Jesus washing Peter’s feet, 1852-56, Tate

The second half of the century was the era of artist-designed frames, but it was catalyzed by the pioneering and innovatory patterns developed by Ford Madox Brown and D.G. Rossetti. These were astonishingly radical when compared, for instance, to Lawrence’s frames. They did not borrow from contemporary architecture, interior design or applied arts, as had most frames before the mid-19th century; they revived ancient practices, such as gilding directly onto oak wood, with no gesso layer, and straight (or ‘butt’) joints instead of mitres, but they also used completely new geometric mouldings and ornaments, setting curved and linear profiles in tension, and roundels, lozenges and squares.

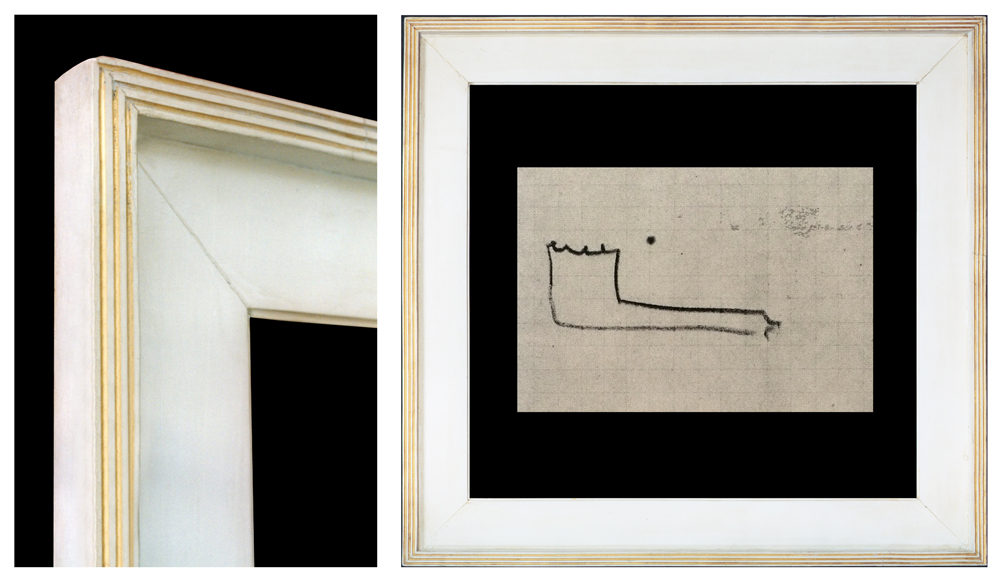

Degas, detailed of white fluted frame, 1870s, with the artist's design for this moulding

This use of geometric shapes, rather than classical architectural or organic structures and motifs, influenced the Impressionists’ early frames, notably those of Degas; his reeded mouldings may well have been stimulated by those of Brown and Rossetti – as were the many other variations on reeding of the later 19th century, on works by Whistler, the Swedish Anders Zorn, and the Belgian Theo van Rysselberghe, etc. Even the Impressionists’ dealer, Durand-Ruel, was influenced into commissioning a pared-down adaptation of a Louis XVI frame, where NeoClassical ornament was married with a version of another of Degas’s designs.

Monet, The cliffs at Pourville, 1882, Art Institute of Chicago

Unfortunately the collectors who were avant-garde enough to invest in Degas and Monet were frequently not enough so to swallow their frames, and a counter-movement began amongst dealers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries to reframe these paintings – usually in antique Baroque French frames, producing the combinations we know so well today. Durand-Ruel himself prudently developed a revival French Régence frame with moulded ornament (above), which might be more acceptable to his American clients, with their Renaissance- and Baroque-style palaces and collections of antique European furniture. The British dealer, Joseph Duveen, reframed Old Master paintings in a similar way – although he invested in exquisitely-carved versions of Baroque French frames, produced for him by master sculptors in Paris and London.

Frederic, Lord Leighton, The last watch of Hero, c.1887, Manchester City Art Gallery

There were other types of artists’ frames which were perhaps more palatable to their purchasers; for instance, the classical aedicules, tabernacles and related revival patterns designed by painters such as Lord Leighton, Alma Tadema, Edward Poynter and Burne-Jones for their work. Because they were contemporary and classicizing they conveyed the right sense of grandeur for the paintings they contained, and for the interiors they were destined for (often the palaces of British industrialists, the analogues of the American chateaux). They also reflected the great municipal buildings of the Victorian age: the town halls, the museums, and some libraries, for which classicism was generally thought more suitable, Gothic being the languages of churches and schools (the palace of Westminster is a notable exception to this). A French equivalent of these British ‘Olympian’ artists and their temple-like frames was Gustave Moreau; several examples of his classical aedicules remain in the Musée Gustave Moreau.

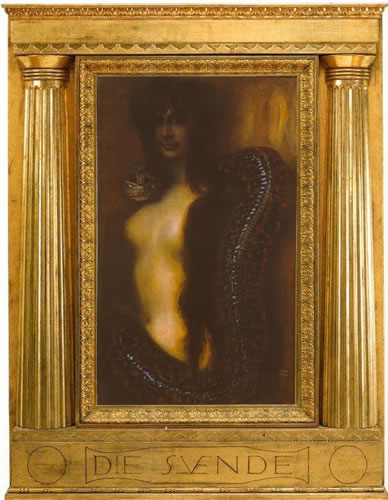

Franz Stuck, Die Suende, 1893, Neue Pinakothek

The classical frames of Franz Stuck were equally calculated to lend his paintings resonance and authority, and perhaps the respectability conveyed by the style in works such as Die Suende (Sin). However, Stuck’s designs, and those of the other Secessionists, have been remade in a way which is less wedded to classical proportions and ornament than those of the British ‘Olympians’; their use of simplified panels, flat planes and inscribed decoration is characteristic from the eclectic approach of the later 19th century, containing elements of Art Nouveau, and also looking towards the more radical simplification of the art deco style. Max Klinger’s work took even more radical liberties with the architectural structure of a classical aedicule, slimming columns into defining struts, and continuing the painting over the area of pilasters and entablature; it was further broken down in Klimt’s designs for his frames.

Later 19th century artists’ frames were distinguished not only by form, but – like Gothic, Renaissance, and Spanish Baroque frames – by colour. The Impressionists, not content with using the most simple profiles, such as the reeding initiated by the Pre-Raphaelites, also experimented with colour. This is generally linked to the work of a chemist, Michel-Eugène Chevreul, in his book, The principles of harmony and contrast of colours and their application to the arts (1839), although there is no evidence that any group of artists before Seurat and Signac knew of his experiments, except as they were filtered through another book by Charles Blanc in 1867 (pp. 598-99).

Degas, detail of green reeded frame, 1870s

Other stimuli for the Impressionists’ use of coloured frames have been cited as the established use of coloured mounts for drawings and prints; Japanese hanging scrolls mounted on differently-coloured papers and silks, imported with the opening up of the Far East to trade from 1858; and Pissarro’s and Monet’s stay in London in 1870-71, where colour division and complementaries were already much discussed. Whatever their source few, sadly, have survived: mainly those of Degas, who policed his work vigilantly. At least one white fluted frame still (probably) exists and there are a couple of original green reeded frames (above). White frames first appeared (on innovatory neutral-coloured walls) in the third Impressionist exhibition of 1877; Mary Cassatt showed work in green and vermilion frames in 1879; and in 1880 several artists used frames complementary to the main colour of the painting. Pissarro’s room extended colour outward from the work (prints with purple frames and yellow mounts) to the walls – lilac – picked out in yellow, and was emulated by Whistler in London, in 1883 and 1884.

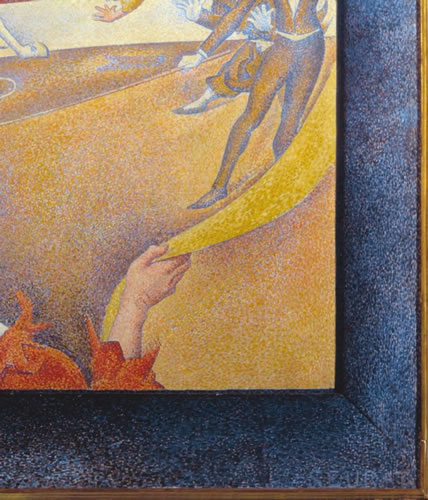

Seurat, Le cirque, 1891, Musée d’Orsay

Seurat took up the idea of white frames and coloured margins to set off his paintings; by 1888 the margins had developed colours complementary to the neighbouring areas of paint, to enhance the optical combinations of painted ‘taches’ which characterized his pointilliste style. In Le cirque, the effect illustrates the artist’s wish both to present his painting as a light-filled stage with a dark proscenium, and (like the Pre-Raphaelites) to create an indivisible whole work of art. Coloured and pointilliste borders were taken up in Belgium, by the members of Les XX. Van Gogh also produced paintings with coloured borders: either wide and decorative, giving a greater sense of the Japanese prints he was recasting, or narrow and complementary to the painting.

Jan Toorop, Song of the times, 1893, Kröller- Müller Museum, Otterlo, with engraved and painted wooden frame

Les XX were not only, nor perhaps not primarily, interested in the effect of complementary colours and tones; they were aesthetes and Symbolists – like Toorop, Fernand Khnopff and Hans Thoma - for whom the frame was an expressive element of the work of art, and who might continue the composition over the actual moulding (as above), or through the form and structure of the frame and the resonances it produced.

The 20th & 21st centuries

Glyn Philpot (1884-1937) Oedipus, 1931-32, The National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

The ornamental and symbolic effects of the painted frame were continued into the 20th century in the work of artists such as Georges Rouault, but many other artists during the first quarter of the new century used coloured or patterned finishes in a purely decorative way - to differentiate their work from academic pictures in conventional gilded frames, to achieve an individual and idiosyncratic look, and to create a modern and minimalist setting which would bind their paintings to contemporary interiors. At the same time movements surfaced which continued to find different ways of exploiting the possibilities which lay waiting in this liminal area: for example, the Futurists, who wanted to portray the speed and technological excitement of the early 20th century, as in Giacomo Balla’s Abstract speed and sound, 1913-14.

Strangely, in the light of this continual trickle of innovation, the later two-thirds of the century saw a sustained movement by both artists and curators to remove the frame altogether (William Seitz, for example, took all the frames off Monet’s works in a 1960 exhibition, regardless of what the artist himself would have thought of such an action, and John Bratby had labels printed for the backs of his paintings forbidding ‘philistine encroachment on the periphery of the picture-surface’). A century after Balla’s work, it might have seemed that the battle of the frame to survive had been lost in the galleries of modern art, and was only won on the domestic front. But, while living artists such as Howard Hodgkin undercut the perpetually renewed appreciation of the frame’s expressive capabilities by ignoring the differences between border and canvas altogether, others such as Chris Wilkinson are capable of producing a sculptural hymn to the frame, and its power to isolate and focus on the artist’s vision.

Royal Academy Summer Exhibition 2014

And for many of those artists, the frame still remains a primary method for separating their depicted worlds from the reality of the spectator, providing an area of transition between one world and the other, harmonizing their work with the interiors where it may hang, protecting it, and distinguishing it from those of others on an exhibition wall. For antique paintings the frame works even harder, recreating something of the historical and social setting, indicating the original purpose and function of a painting, expanding upon the meaning of the subject, and restoring aesthetic balance and harmony. In the end, there are scarcely any paintings that would not gain presence and authority from a well-chosen frame.